The year 2020 was a watershed moment for the fossil fuel sector. Faced with a global pandemic, severe demand shocks, and a shift towards renewable energy, experts warned that nearly $900 billion worth of reserves–or about one-third of the value of big oil and gas companies–were at risk of becoming worthless.

Big Oil appears to have mostly resigned itself to this fate.

Last year, British oil giant BP Plc. sent shockwaves through the oil and gas sector after it declared that the world was already past Peak Oil demand. In the company’s 2020 Energy Outlook, chief executive Bernard Looney pledged that BP would increase its renewables spending twentyfold to $5 billion a year by 2030 and “… not enter any new countries for oil and gas exploration.”

BP–company that doubled down on its aggressive drilling strategy right after the historic 2015 UN Climate Change Agreement--finally appeared to throw in the towel, saying, “..concerns about carbon emissions and climate change mean that it is increasingly unlikely that the world’s reserves of oil will ever be exhausted.” BP went on to announce one of the largest asset writedowns of any oil major after slashing up to $17.5 billion off the value of its assets and conceded that it “expects the pandemic to hasten the shift away from fossil fuels.”

It’s a refrain that was shared by several oil executives, with Royal Dutch Shell CEO Ben van Beurden declaring that we were already past peak oil demand.

The vast majority of oil and gas companies, including supermajors such as ExxonMobil, Chevron Inc., announced deep spending cuts in 2020, with Capex reduction exceeding $85 billion.

Yet, an ironic twist of fate might mean that rather than huge oil and gas reserves remaining buried deep in the ground, the world could very well run out of those commodities in our lifetimes.

Indeed, delving deeper into the global oil and gas outlook suggests that it’s peak oil supply, not peak oil demand, that’s likely to start dominating headlines as the years roll on.

Peak Oil Demand

Peak Oil Demand

When many analysts talk about Peak Oil, they are usually referring to that point in time when global oil demand will enter a phase of terminal and irreversible decline.

According to BP, this point has already come and gone, with oil demand slated to fall by at least 10% in the current decade and by as much as 50% over the next two. BP notes that historically, energy demand has risen steadily in tandem with global economic growth with few exceptions; however, the COVID-19 crisis and increased climate action might have permanently altered that playbook.

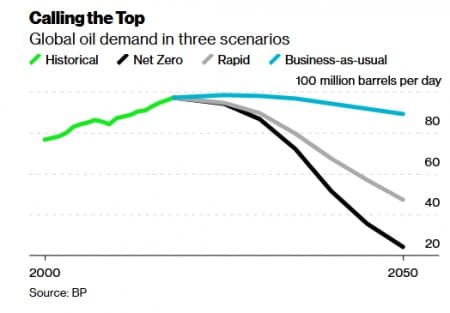

BP has modeled 3 possible scenarios for the future of global fuel and electricity demand: Business as Usual, Rapid Transition, and Net Zero. Here’s the kicker: BP says that even under the most optimistic scenario where energy policy keeps evolving at pretty much the pace it is today (Business as Usual) oil demand will still suffer declines– only at a later date and at a slower pace compared to the other two scenarios.

The oil bulls, however, can take comfort in the fact that under the Business-as-Usual scenario, BP sees oil demand remaining at 2018 levels of 97-98 million barrels per day till 2030 before falling to 94 million barrels per day in 2040 and eventually to 89 million barrels per day three decades from now. That’s a loss in demand of less than 1% per year through 2050.

However, things could look very different under the other two scenarios that entail aggressive government policies aimed at reaching net-zero status by 2050 as well as carbon prices and other interventions aimed at limiting global warming.

Under the Rapid Transition scenario (moderately aggressive), BP sees oil demand falling 10% by 2030 and nearly 15% under Net Zero (most aggressive).

In other words, the decline in oil demand is bound to be catastrophic for the industry over the next decade under any other scenario other than Business-as-Usual.

Luckily, this is the scenario that’s likely to dominate over the next decade.

David Blackmon, a Texas-based independent energy analyst/consultant, has told Forbes that many analysts are skeptical about BP’s grim outlook. Indeed, Blackmon says a “Business as Usual” scenario appears the most likely path for the time being, given the time the global economy might take to recover from Covid-19 as well as the trillions of dollars that would be required to implement the other two cases.

Further, it’s important to note that BP made those projections before Covid-19 vaccines had entered the fray. With countries such as the United States having rolled out successful vaccination programs and even started reopening their economies, the global oil and gas outlook has improved considerably.

Peak Oil Supply

Though less frequently discussed seriously, Peak Oil Supply remains a distinct possibility over the next couple of years.

In the past, supply-side “peak oil” theories mostly turned out to be wrong mainly because their proponents invariably underestimated the enormity of yet-to-be-discovered resources. In more recent years, demand-side “peak oil” theory has always managed to overestimate the ability of renewable energy sources and electric vehicles to displace fossil fuels.

Then, of course, few could have foretold the explosive growth of U.S. shale that added 13 million barrels per day to global supply from just 1-2 million b/d in the space of just a decade.

It’s ironic that the shale crisis is likely to be responsible for triggering Peak Oil Supply.

In an excellent op/ed, vice chairman of IHS Markit Dan Yergin observes that it’s almost inevitable that shale output will go in reverse and decline thanks to drastic cutbacks in investment and only later recover at a slow pace. Shale oil wells decline at an exceptionally fast clip and therefore require constant drilling to replenish lost supply.

Indeed, Norway-based energy consultancy Rystad Energy recently warned that Big Oil could see its proven reserves run out in less than 15 years, thanks to produced volumes not being fully replaced with new discoveries.

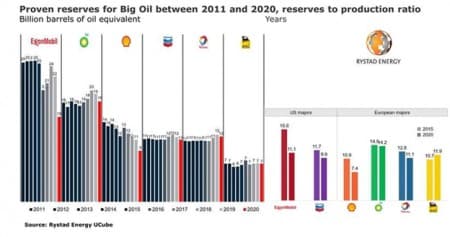

According to Rystad, proven oil and gas reserves by the so-called Big Oil companies, namely ExxonMobil, BP Plc., Shell, Chevron, Total, and Eni S.p.A are falling, as produced volumes are not being fully replaced with new discoveries.

Dwindling reserves

Massive impairment charges saw Big Oil’s proven reserves drop by 13 billion boe, good for ~15% of its stock levels in the ground, last year. Rystad now says that the remaining reserves are set to run out in less than 15 years unless Big Oil makes more commercial discoveries quickly.

The main culprit: Rapidly shrinking exploration investments.

Global oil and gas companies cut their capex by a staggering 34% in 2020, in response to shrinking demand and investors growing weary of persistently poor returns by the sector.

The trend shows no signs of moderating: First quarter discoveries totalled 1.2 billion boe, the lowest in 7 years with successful wildcats only yielding modest-sized finds as per Rystad.

ExxonMobil, whose proven reserves shrank by 7 billion boe in 2020, or 30%, from 2019 levels, was the worst hit after major reductions in Canadian oil sands and US shale gas properties.

Shell, meanwhile, saw its proven reserves fall by 20% to 9 billion boe last year; Chevron lost 2 billion boe of proven reserves due to impairment charges while BP lost 1 boe. Only Total and Eni have avoided reductions in proven reserves over the past decade.

Climate activism

Yet, policy changes by Biden’s administration, as well as fever-pitch climate activism, are likely to make it really hard for Big Oil to go back to its trigger-happy drilling days.

In his first three months in office, Joe Biden has rejoined the Paris climate agreement, scuppered a controversial oil pipeline, suspended fossil fuel leases on public land, proposed unprecedented investment in clean energy, and started to reverse many of his predecessor’s regulatory rollbacks.

In a virtual climate summit with 41 world leaders last month, President Joe Biden unveiled an ambitious 10-year Climate Plan that has proposed cutting U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52% by 2030. That represents a near-doubling of the U.S. commitment of a 26-28% cut under the Obama administration following the Paris Agreement of 2015.

Biden had even proposed a carbon tax, though it was conspicuously absent in his latest climate policy.

Meanwhile, the world’s biggest asset manager BlackRock, has been doubling down on oil and gas divestitures.

Back in 2019, BlackRock declared its intention to increase its ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) investments more than tenfold from $90 billion to a trillion dollars in the space of a decade.

But now the firm is pushing out the goalposts on climate action and wants companies that he invests in to disclose how they plan to achieve a net-zero economy, which he has defined as eliminating net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. BlackRock plans to put oil and gas companies under the clamps by creating a “temperature alignment metric” for both its public equity and bond funds with explicit temperature alignment goals, including products aligned to a net-zero pathway.

Climate activists, including the Sierra Club, have been bombarding BlackRock and Vanguard with calls and emails urging them to vote against Exxon Mobil’s CEO Darren Woods, saying Exxon’s board “needs an overhaul” to better manage climate risks and guide the company to a low carbon future.

Business unusual

During last month’s CERAWeek by IHS Markit energy conference, it became abundantly clear that Big Oil wants to focus not so much on curtailing oil and gas production but rather on mitigating the impact of its carbon and greenhouse gas emissions.

According to Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods and Occidental Petroleum‘s Vicky Hollub, reducing carbon emissions from fossil fuels and not the actual use of fossil fuels, offers the best way to combat climate change.

Interestingly, both CEOs have stressed that the world still needs oil and gas, and governments need to focus on mitigating global warming using technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) instead of attacking fossil fuels.

Nevertheless, even the biggest hardliner of them all, Exxon Mobil, has markedly changed its tune from just a few years back.

During the company’s 2021 Investor Day, CEO Darren Woods outlined the company’s energy transition strategy, including plans to trim production growth and boost cash flows in a bid to support a growing dividend. Exxon revealed that it plans to hold production flat from 2020 levels through 2025 at 3.7M boe/day, good for a 26% cut from the 5M boe/day estimate for 2025 it released just a year ago.

In other words, it’s going to be really hard for Big Oil to continue with business as usual despite an oil price recovery, meaning the prospects of a major oil supply crunch remains very real.

![[Latest] Global Data Center CPU Market Size/Share Worth USD 48.9 Billion by 2033 at a 15.2% CAGR: Custom Market Insights (Analysis, Outlook, Leaders, Report, Trends, Forecast, Segmentation, Growth, Growth Rate, Value)](https://energy.asia/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/global-data-center-cpu-market-2024-2033-by-billion--120x86.png)