Surging diesel prices may be squeezing farmers across India’s vast hinterlands, but they’re also kindling the nation’s knack for improvisation.

Frugal workarounds, or hacks in modern parlance, are celebrated in Indian culture and known colloquially as jugaad. And if the innovativeness of farmers like Sarvesh Kumar Verma is anything to go by, this can-do attitude could pose a threat to demand for the nation’s most widely used petroleum product.

Frustrated over rising diesel prices, the rice and potato grower decided to hunt for an alternative. Verma found what he was looking for in his kitchen: a canister of liquefied petroleum gas used for cooking. After tinkering with the diesel-fueled pump that irrigates his fields in Uttar Pradesh state, he soon had it running smoothly on LPG, cutting his energy costs by about a third.

“The best part is that there is no smoke,” the 40-year-old farmer said. “I’m now helping some other farmers in my village to switch their pumps to LPG.”

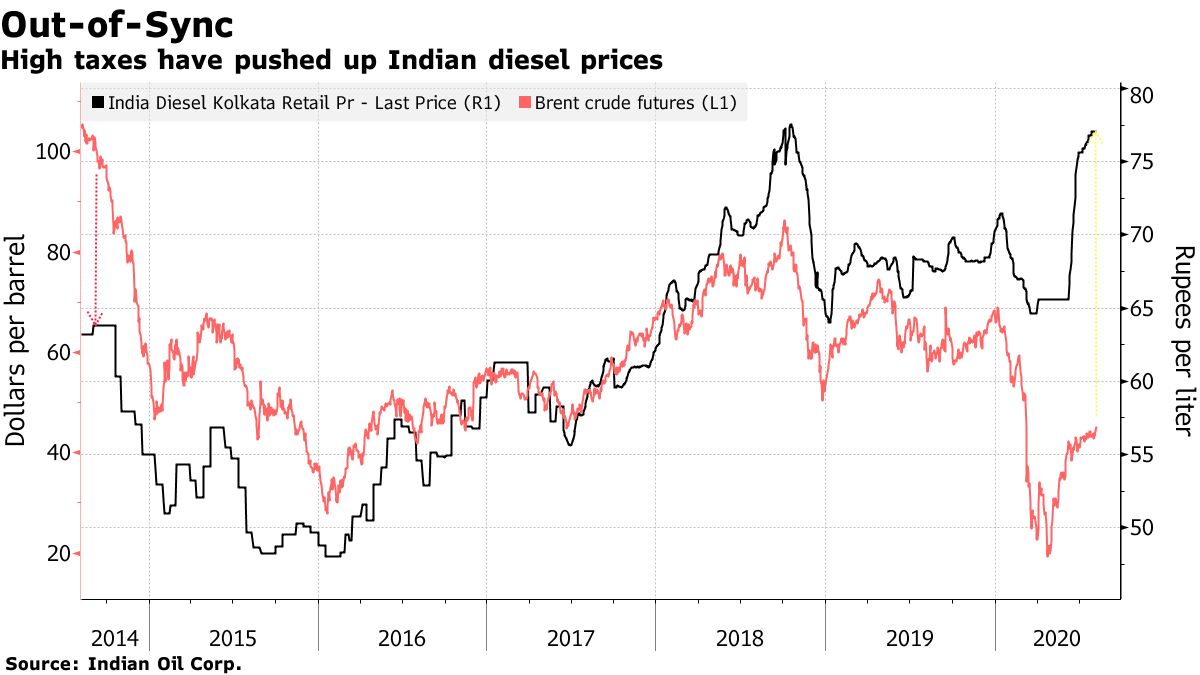

Verma’s exasperation was driven by diesel prices bloated by a fivefold jump in federal government taxes over the last five years. The retail price of the fuel in Kolkata and other Indian cities has surged this year, even as the coronavirus pummeled the economy. It’s now 20 percent higher than in mid-2014 when Brent crude was fetching more than US$100 a barrel.

While no one is predicting the imminent demise of diesel in India, LPG is one of several energy sources that look set to chip away at the dominance of the fuel that accounts for around 40 percent of the country’s oil consumption.

In agriculture — which accounts for about 13 percent of India’s diesel consumption – solar power and compressed natural gas are other potential substitutes. Small-scale solar with battery storage may be the best option for Indian farmers in the long run, while switching to CNG would be trickier as it’s not as available as LPG, said Vandana Hari, founder of consultancy Vanda Insights in Singapore.

“Economics will probably be a strong driver for the conversion of diesel pumps to LPG” and it’s also desirable from an environmental perspective as gas is cleaner, she said. “But in the big picture, it’s not good for the Indian refining sector, which is designed to maximize diesel production.”

Perhaps the bigger threat to the fuel comes from transport. India’s trucks, buses and trains run on diesel, with the sector accounting for more than two-thirds of the nation’s consumption. The rise of natural gas and electric vehicles will crimp diesel demand over the longer-term, but the coronavirus is adding to that pressure by cutting economic activity and making people more likely to use personal cars and motorbikes for fear of getting infected.

“In transportation, personal solutions are making more strides into mass mobility,” said R. Ramachandran, refineries director at Bharat Petroleum Corp. “These are bigger problems for diesel.”

Sales of diesel at India’s three biggest fuel retailers fell 21 percent in July from June, according to preliminary data from officials with direct knowledge of the matter, in a stark reversal from a recovery in the previous months. Other economic activity indicators are also beginning to flatline as some of the country’s most-industrialized states reimpose lockdowns to stem COVID-19.

Refiners Responding

The country’s fuel processors are responding to the new realities, however. Reliance Industries Ltd., which operates the world’s biggest oil refining complex, is looking at batteries for electric vehicles and hydrogen for transport, Chairman Mukesh Ambani told shareholders last month. Any excess diesel and gasoline can be used for petrochemical production, he said.

State-owned Indian Oil Corp., the country’s biggest refiner, said it’s working on cleaner and cheaper fuels to replace diesel for generators and water pumps. “We’re coming up with a low-sulfur heavy stock, which will absolutely comply with the emissions of generator sets, and will meet green standards,” said S.S.V. Ramakumar, director of research and development at Indian Oil.

A lack of supply of LPG – commonly used for cooking in India and sometimes subsidized by the government – may also limit the extent to which it can be used to replace diesel. India imports more than half of its LPG needs.

“Where do you get the LPG for use in the pumps?” Ramakumar said. “Everything has its pros and cons,” he said, adding that there are also other cheaper options such as CNG and blending ethanol into fuels. – Bloomberg